Manu Balachandran is a writer for Forbes India, based in Bengaluru. At Forbes India, Manu writes on automobiles, aviation, pharmaceuticals, banking, infrastructure, economy and long profiles among many others. He also moderates many of Forbes India's CEO and CXO events and hosts Capital Ideas, a podcast on the most riveting success stories from the business world. He has previously worked with Quartz, The Economic Times and Business Standard in Mumbai and New Delhi. Manu has a master's degree in journalism from Cardiff University and a degree in economics from the Loyola College. When not chasing stories, he is most likely obsessing over Formula 1 (Read: Lewis Hamilton), historical events and people, or planning long weekend drives from Bengaluru

Abandoned half-constructed buildings on farmland, where two types of crops were grown a year, with dug-up approach roads lined on either side with weeds and thickets. Image: Vikas Chandra Pureti for Forbes India

I t was supposed to be the city of dreams.

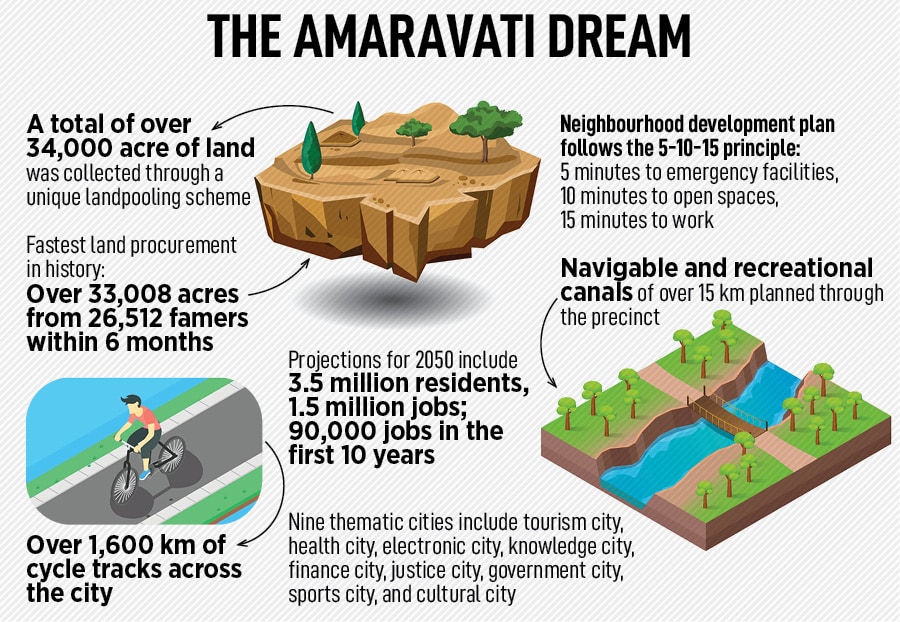

A cityscape boasting solar panels on every rooftop, offices on the riverfront, hospitals accessible in less than 10 minutes, water taxis, parks and cycling tracks with shaded walkways for its 3.5 million citizens. The tropical weather may have been a dampener, but the large green cover was likely to make up for it.

At a time when India’s metropolises struggle to breathe and population skyrockets, making many of them increasingly unlivable with every passing day, Amaravati, located 300 km from Hyderabad, was being built as a ‘happy’, ‘liveable’ and ‘sustainable’ city for the future. It was the first time in many decades that a city was being built ground up in the country, offering a unique opportunity to address fundamental issues that plague India’s metropolises.

There was good reason to pick Amaravati, a fertile land surrounded by hills of the Eastern Ghats, and lying very close to the Krishna river, India’s third longest river. For one, water shortages wouldn’t pose a concern. The city also lies halfway between Andhra Pradesh’s (AP) commercial capital of Vijayawada and the agricultural hub of Guntur, making it accessible by road and rail. Amaravati had, many centuries ago, been a hub of Buddhism and the seat of power for the Satavahana dynasty. It also offered the AP government an opportunity to revive a lost city, as it began scouting for a new capital city after the bifurcation of the state in 2014.

In 2014, the erstwhile state of AP was split into Andhra Pradesh and Telangana, with Hyderabad serving as the common capital until 2024. After this date, it would remain Telangana’s lone capital, forcing AP to scout for a new one.

But a decade since the decision to make the fertile and ancient land into its new capital city, Amaravati remains a dream, having run into issues that plague many Indian cities. The lack of political willpower, shifting priorities, and political mudslinging have left it like a ghost city of sorts, with the only functional buildings being the Andhra Pradesh High Court and its legislative assembly. Those too were supposed to be temporary structures with the original plan looking to house the court in a Buddhist stupa-shaped building, while a diamond-shaped building would house the legislative assembly complex.

Today, abandoned half-constructed buildings adorn what was once farmland, where two types of crops were grown a year, while dug-up approach roads lined on either side with weeds and thickets welcome you to the city. There are very few streetlamps, and venturing out in the dark is a scary proposition, even between the functioning court and legislative assembly buildings. Following the new government coming to power, the past week has seen many excavators and tractors working overtime to clear the mess. But roads continue to terminate abruptly and are often filled with slime, making commute an ordeal.

Along the way, on the routes where excavators have cleared the overgrowth, you can spot neatly made drainage systems that are now full of sand and muck, highlighting what seemed like a clear intention to build a well-planned city. “You will see hectic activity as new roads will be laid and transport and other facilities created,” said Chandrababu Naidu, the recently returned chief minister (CM) of Andhra Pradesh and the mastermind behind Amaravati, on June 15. Naidu, from the Telugu Desam Party (TDP), was sworn in as CM on June 12, in an event attended by Prime Minister (PM) Narendra Modi to Home Minister Amit Shah.

The recently concluded elections in India made Naidu a kingmaker, where Modi needs Naidu’s support to keep his government intact, after the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) fell short of an absolute majority in the Lok Sabha. This means Naidu now has the political muscle to restart the shelved project, this time with enough financial support from the central government.

Along the routes excavators clear the overgrowth, you can spot neatly made drainage systems that are now full of sand and muck, highlighting what seemed like a clear intention to build a well-planned city. Image: Vikas Chandra Pureti for Forbes India

Amaravati’s master plan was developed by London-based Foster + Partners and claims to be one of the most sustainable cities in the world. The plan envisages a governmental complex in the city’s centre, with a strong urban grid surrounding it. A green patch, inspired by Lutyens’ Delhi and New York’s Central Park, runs through its length, with 60 percent of the area occupied by greenery or water.

The city’s transportation needs will be met by electric vehicles (EVs), water taxis, and dedicated cycle routes, along with shaded streets and squares that will encourage people to walk through the city. Then there are 13 urban plazas, the first of which will be the legislative assembly building, sitting within a large freshwater lake. The city is divided into nine zones, namely government, sports, health, electronics, tourism, knowledge, finance, justice, and media city. The city also wants to build an inclusive community that follows a 5-10-15 principle: 5 minutes to emergency facilities, 10 minutes to open spaces, and 15 minutes to work.

Amaravati was first announced as the capital in 2015, soon after Naidu became the CM following TDP’s victory in the 2014 AP state elections. The decision to make Amaravati the capital was accepted by all political parties in the state, and it only helped that Naidu was also supporting Modi’s National Democratic Alliance (NDA) government at the centre. It was the PM who laid the foundation for the new city and, over the next five years, the state government spent over Rs 10,000 crore towards building the city’s infrastructure.

More than 34,000 acres of land was collected through a unique land pooling scheme towards setting up what Naidu had called “people’s capital”; in all, 29,881 farmers, big and small, parted with their lands. For every acre given to the government under the dry land category, farmers would be reciprocated with 1,000 square yard of residential land with another 250 square yard of commercial land.

Those who donated fertile or irrigated agricultural land would be given 1,000 square yard of residential land and 450 square yard of commercial land once the projects took shape. In all, 20,490 farmers donated land of less than 1 acre, while 5,227 farmers parted with land between 2 and 5 acre. Those who gave away land of more than 5 acre stood at over 800, with 25 farmers giving away more than 25 acre of land.

Additionally, since the farmlands were being taken away, the government also began paying an annuity for lost income that ranged between Rs 30,000 and Rs 50,000, with a 10 percent enhancement every year. The capital city was to be spread over 216 sq km, and house over 3.5 million people with the completion set for 2029. The Naidu government had anticipated a capital expenditure of Rs 51,000 crore for the first phase of its development.

The master plan divided the capital region into three areas, a larger Amaravati Capital Region covering the Krishna and Guntur districts, the capital city of Amaravati, and the seed capital area, or the core capital area that would comprise the financial and IT hubs. By October 2015, a Singapore-based consortium of Ascendas Singbridge and Sembcorp Development submitted a proposal to become the master developer of the 6.84 sq km area, which would form the commercial and seed core of Amaravati. The city would also have a 22-km Krishna waterfront, which would house the city’s civic core and central business district (CBD).

“The idea was to have 40 percent of the land for infrastructure, roads, and greenery while 60 percent of the land would be given back to the farmers, while another 10,000 acre would remain with the government,” says G Tirupati Rao, the convener of the Amaravati Pariraskshana Samithi (Committee to protect Amaravati), a committee to protect the interest of the farmers in Amaravati, while speaking to Forbes India. “Even though the Opposition cried foul, in 2018, the National Green Tribunal had also given its go-ahead for the project.”

The only functional buildings being the Andhra Pradesh High Court and its legislative assembly which are supposed to be temporary structures. Image: Vikas Chandra Pureti for Forbes India

Work began in 2015, and according to the detailed project report, Rao says, the infrastructure cost alone included Rs22,000 crore worth of work, with the Naidu government completing projects worth Rs 10,000 crore by the time the state went into polls four years later in 2019. That included roads and new office buildings, while private institutions including SRM and VIT were allotted land to set up their facilities.

In 2019, Naidu lost power in the state, with political rival YS Jagan Mohan Reddy securing a landslide victory in the elections. The change of guard meant that ongoing projects in Amaravati came to a standstill, with even the World Bank and the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB) announcing their withdrawal from the project. The World Bank had committed a loan of $300 million (Rs 2,100 crore) while AIIB had promised $200 million (Rs 1400 crore). The consortium of Ascendas Singbridge and Sembcorp Development also withdrew from the project.

Soon enough, new CM Reddy, who had alleged rampant corruption in the Amaravati project, decided to cancel it. He, instead, proposed a three-capital formula: Vishakhapatnam as the administrative capital, Kurnool as the judicial capital and Amaravati as the legislative capital.

Reddy’s decision to scrap the Amaravati project meant that farmers who had given up their lands were up in arms, conducting protest marches across the state and even being beaten up by the police. “People of Amaravati believe that Reddy did not want to go ahead with this project because he did not want a project by Naidu to succeed, as it was seen as his pet project,” adds Rao, who led the agitation in Amaravati for over 1,600 days.

Finally, in 2022, after various court battles, the AP High Court ruled that the government could not abandon the development of Amaravati, especially since they had signed an agreement, and asked the government to develop it within six months. The high court also asked the government to develop the nine theme cities, asking them to stick to the capital city’s master plan prepared by Naidu.

The Reddy government went to the Supreme Court, which stayed the high court’s decision. “All the materials were being stolen and roads were being dug up,” Rao says about the Reddy’s regime. “There were projects that were 90 percent complete, awaiting electricity and water supply. Those weren’t given. In many houses that were built, the Reddy government decided to paint them with their party colours.”

Roads continue to terminate abruptly and are often filled with slime, making commute an ordeal. Image: Vikas Chandra Pureti for Forbes India

Since he took charge, Naidu has once again reiterated his plan to make Amaravati the capital city, debunking Reddy’s three-capital plan.

That’s precisely why investors are now flocking to Amaravati to pick up whatever land they can grab as expectations remain sky-high about his regime. “Before elections, you would hardly get a call for a plot of land in the core Amaravati region,” says Kolisetty Vamsi Krishna, a real estate developer and a committee member of the National Real Estate Development Council (NAREDCO). “Now you are getting over 30 calls a day. The same person [seller] would get at least three calls a day. That’s the rush and everyone wants to cash in. As far as prices go, we don’t know where the prices will settle.”

Sarath, a former journalist from Vijayawada, says that in 2022, a square yard of land in Amaravati was worth Rs 15,000, which has since jumped to Rs 35,000 since Naidu’s party swept the Andhra Pradesh elections. Anticipations are also fuelled by the fact that Naidu has full majority in the state, and he remains a key player in national politics. “It was Rs 35,000 yesterday,” Sarath says. “That number is only expected to grow further once the government is in power.”

Naidu’s resounding victory—voter turnout was around 82 percent for the state elections held on May 13—was also an indication of people’s growing anger with Reddy’s government, which was perceived as inaccessible and spending poorly on development, instead relying on direct benefit transfer schemes. “This time, people came from abroad and very far, and some even stood in line until 10 PM because they were fed up with the government,” says Tadi Shakuntala, a former mayor of Vijayawada and a TDP member. “Reddy was not active in developing industry and many investments moved out of the state. Steel and sugar industries suffered as a result.”

“Reddy’s despise for Amaravati stems from the belief that the Kamma community, to which Naidu belongs, was benefitting from the project,” says an independent builder in AP. “It can’t be established, although a committee set up by the government had pointed to environmental problems with the Vijayawada-Guntur region, and that it was perhaps not the best location for a capital. So, in that sense, the choice of Amaravati was puzzling to many.”

A report of the expert committee headed by former bureaucrat KC Sivaramakrishnan in 2014 to study alternatives for Andhra Pradesh’s new capital had said that Vijayawada, Guntur, and Nellore are especially prone to flooding. “Hence, a very cautious choice has to be made around these locations as capital zones,” the report had said.

Meanwhile, despite the government’s mighty push, a revival of Amaravati isn’t going to be an easy affair, even though the Naidu government has set an ambitious target of 30 months to complete projects that were previously 90 percent complete. "Amaravati will be our capital,” Naidu said, soon after being sworn in as CM. “We will pursue constructive politics, and not politics of vendetta. Visakhapatnam will be the commercial capital of the state. We will not play games with people, like trying to have three capitals and such devious activities.”

The Naidu government had invited tenders worth Rs48,000 crore during the first phase of the capital city project, and made payments of nearly Rs9,000 crore for the work. “The government will stick to the old master plan designed by Foster + Partners,” said P Narayana, who took charge as Minister for Municipal Administration & Urban Development (MA&UD), on June 16.

In the process, though, Amaravati could also pose some trouble for Hyderabad, a city that Naidu had earlier helped build into a global technology hub before the state bifurcation in 2014. “The volume of residential real estate launches in the city may also rationalise as investors and buyers scout for competitive opportunities in AP, which is expected to witness a surge in development along the new growth corridors,” says real estate consultancy firm Anarock. “AP's potential development can be a double-edged sword for Hyderabad real estate. However, the overall impact is likely to be positive as AP's growth could spark a ripple effect, attracting businesses and investors to the entire region.”

Whether that happens or not, Naidu is most certainly a man on a mission and Amaravati could cement his legacy. In the nearly two millennia that it has existed, Amaravati has seen many kings come and go. Perhaps this time around, it might be gearing up for lost glory, with a kingmaker in charge.